It Don’t Take Sherlock to Know; When the Wind Don’t Blow, The Power Don’t Flow

STT has – just once or twice – smashed the myth that wind power can provide a meaningful supply of electricity (ie power “on-demand”) – and relegated to the fiction aisle the the wind industry’s “playbook”, where you’ll find, in bold print, the oft-told furphy about wind farms “powering” 10s of thousands of homes.

At STT the term “powering” means exactly what it says: that when someone – at any time of the day or night – in any and all of the thousands of homes claimed to be “powered” by wind power – flicks theswitch the lights go on or the kettle starts boiling.

The wind industry never qualifies its we’re “powering thousands of homes” mantra by saying what it really means: that wind power might be throwing a little illumination or sparking up the kettle in those homes every now and again – and that the rest of time their owners will be tapping into a system of generation that operates quite happily 24 x 7, rain, hail or shine – without which they’d be eating tins of cold baked beans, while sitting freezing (or boiling) in the dark.

Here’s a little collection of posts busting that and other wind power myths in Australia:

- South Australian Wind Power “FAILS”

- Wind Power Myths BUSTED

- More Australian Wind Power “FAILS”

- Where will you be when the lights go out for good?

- The Gambler

- The “Great Oz” has spoken: the wind will no longer be “intermittent”

- Herald Sun’s Terry McCrann: “The Climate Spectator’s a joke!”

And hammering the same myths, elsewhere around the world:

- Texas Blames Wind Power Slump on (you guessed it) … the Wind

- Germans Blame “Missing Wind” for their Wind Power Debacle

- Brits Rumble Frightening Energy Fact: Wind Power Depends on the (ur, ahem) Wind …

- Why wind power MW will never be equal

- Why Wind Power Will Never be a Serious Alternative to Conventional Power Generation

Now, Andrew Rogers of Energy Matters has done a beautiful number on the same myths, as relentlessly pedalled by the wind industry in Europe. (Oh, and if the graphs are too puny or fuzzy, click on them, they’ll pop up in a new window and you can magnify them from there.)

Wind Blowing Nowhere

Energy Matters

Roger Andrews

23 January 2015

In much of Europe energy policy is being formulated by policymakers who assume that combining wind generation over large areas will flatten out the spikes and fill in the troughs and thereby allow wind to be “harnessed to provide reliable electricity” as the European Wind Energy Association tells them it will:

The wind does not blow continuously, yet there is little overall impact if the wind stops blowing somewhere – it is always blowing somewhere else. Thus, wind can be harnessed to provide reliable electricity even though the wind is not available 100% of the time at one particular site.

Here we will review whether this assumption is valid. We will do so by progressively combining hourly wind generation data for 2013 for nine countries in Western Europe downloaded from the excellent data base compiled by Paul-Frederik Bach, paying special attention to periods when “the wind stops blowing somewhere”. The nine countries are Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Germany, Spain and the UK, which together cover a land area of 2.3 million square kilometers and extend over distances of 2,000 kilometers east-west and 4,000 kilometers north-south:

We begin with Spain, Europe’s largest producer of wind power in 2013. Here is Spain’s hourly wind generation for the year. Four periods of low wind output are numbered for reference:

Now we will add Germany, Europe’s second-largest wind power producer in 2013. We find that Spanish low wind output period 4 was more than offset by a coincident German wind spike. Spanish low wind periods 1, 2 and 3, however, were not.

Now we add UK, the third largest producer in 2013. Wind generation in UK during periods 1, 2 and 3 was also minimal:

As it was in France, the fourth largest producer:

And also in the other five countries, which I’ve combined for convenience:

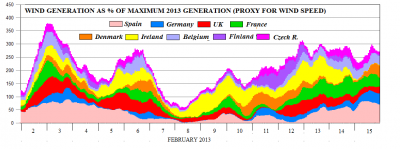

Figure 7 is a blowup of the period between February 2 and 15, which covers low wind period 2. According to these results the wind died to a whisper all over Western Europe in the early hours of February 8th:

These results are, however, potentially misleading because of the large differences in output between the different countries. The wind could have been blowing in Finland and the Czech Republic but we wouldn’t see it in Figure 7 because the output from these countries is still swamped by the larger producers. To level the playing field I normalized the data by setting maximum 2013 wind generation to 100% and the minimum to 0% in each country, so that Germany, for example, scores 100% with 26,000MW output and 50% with 13,000MW while Finland scores 100% with only 222MW and 50% with only 111MW. Expressing generation as a percentage of maximum output gives us a reasonably good proxy for wind speed.

Replotting Figure 7 using these percentages yields the results shown in Figure 8 (the maximum theoretical output for the nine countries combined is 900%, incidentally). We find that the wind was in fact still blowing in Ireland during the low-wind period on February 8th, but usually at less than 50% of maximum.

But even Ireland was not blessed with much in the way of wind at the time of minimum output, which occurred at 5 am. Figure 10 plots the percentage-of-maximum values for the individual countries at 5 am on the map of Europe. If we assume that less than 5% signifies “no wind” there was at this time no wind over an area up to 1,000 km wide extending from Gibraltar at least to the northern tip of Denmark and probably as far north as the White Sea:

During this period the wind was clearly not blowing “somewhere else”, and there are other periods like it.

Combining wind generation from the nine countries has also not smoothed out the spikes. The final product looks just as spiky as the data from Spain we began with; the spikes have just shifted position:

Obviously combining wind generation in Western Europe is not going to provide the “reliable electricity” its backers claim it will. Integrating European wind into a European grid will in fact pose just as many problems as integrating UK wind into the UK grid or Scottish wind into the Scottish grid, but on a larger scale. We will take a brief look at this issue before concluding.

Integrating the combined wind output from the nine countries into a European grid would not have posed any insurmountable difficulties in 2013 because wind was still a minor player, supplying only 8.8% of demand:

But integration becomes progressively more problematic at higher levels of wind penetration. I simulated higher levels by factoring up 2013 wind generation with the results shown on Figure 12, which plots the percentage of demand supplied by wind in the nine countries in each hourly period. Twenty percent wind penetration looks as if it might be achievable; forty percent doesn’t.

Finally, many thanks to Hubert Flocard, who recently performed a parallel study and graciously gave Energy Matters permission to re-invent the wheel, plus a hat tip to Hugh Sharman for bringing Hubert’s work to our attention.

Energy Matters